When the world was at its worst, Matisse was at his best

PHILADELPHIA — Civilization had a total breakdown in the 1930s, which also happened to be the decade when Henri Matisse became most himself. “Matisse in the 1930s,” a groundbreaking exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, presents this miraculous, joyous phenomenon — a great artist, having just turned age 60, fully coming into his own. But the spectacle is haunted by history.

If you want to try to reconcile Matisse’s stream of gorgeous, life-enhancing inventions in those years with the Great Depression, the rise of fascism, civil war in Spain, the Nazis’ demonization of modern art(including Matisse’s) as “degenerate,” the state-sponsored persecution of Jews and the terrifying buildup to the Holocaust, you might as well fold your cards. It is not possible.

You can only remind yourself that Matisse was not in control of world events. In fact, he was barely in control of himself. His intense susceptibility to visual beauty and his acute artistic intelligence had made him, in the eyes of many, a radical. He had spent most of his career out on a ledge, blasted by the high winds of public mockery. But he was a father, a family man, a good citizen, and he yearned for sympathy and respect.

Ledges are lonely places. So for more than a decade, beginning in late 1917, Matisse stepped back from the precipice. He moved from Paris to Nice. He painted smaller canvases — nudes and interiors influenced by Impressionism and Orientalism — modeling spaces and volumes with perspective lines and shifts in tone. I personally adore the work that emerged from Matisse’s “Nice period.” But there is no denying that, by the end of the 1920s, Matisse was becoming repetitive. He was creatively blocked. “In front of the canvas,” he wrote to his daughter, “I have no ideas whatever.”

He needed to up the ante.

“Matisse in the 1930s,” which was organized by Matthew Affron, Cécile Debray and Claudine Grammont, shows us exactly how he did that. It is the most important Matisse exhibition in America for many years.

Matisse was extraordinary in every phase of his career. But it was not until the 1930s that he successfully integrated all the aspects of his originality — in conception, drawing, color, treatment of space, emotional register. In the process he achieved a kind of mastery. The struggle was unrelenting. But everything that followed, right up to the late paper cutouts and the chapel in Vence, would be a kind of playing out of that mastery.

The decade began with three key developments. The first was a series of Matisse retrospectives, all staged consecutively in 1930-31 in Berlin; Paris; Basel, Switzerland; and New York. Retrospectives were rare in those days. Four in two years was unprecedented and a clear sign that the world was catching up with the French artist. He was, as art historian Éric de Chassey writes in the catalogue, “incontestably one of the best-selling and most respected artists of his time.”

“Retrospection” means looking back, thinking about the past. But what Matisse drew from these four retrospectives was that he wanted to look forward. “He wanted to be an artist who opened a path rather than closed it,” writes de Chassey, “a pioneer rather than an inheritor.” The Impressionist space and atmosphere of his Nice period pictures was the past. He needed to leave it behind.

The second key development was travel. In February 1930, Matisse traveled to New York, then proceeded by deluxe train to Chicago, Las Vegas, Los Angeles and San Francisco, before crossing the Pacific Ocean by ship to Tahiti. He made almost no art during this trip. But he absorbed everything. His mind and heart were refreshed.

The third was a commission from Albert Barnes, the American collector and evangelist for modern art. Barnes wanted Matisse to adorn the arched walls of the main gallery in his foundation in Merion, a suburb of Philadelphia. So on a second trip to America that same year, Matisse went there. Relations with Barnes would later become fraught. But the commission, the results of which you can see for yourself if you walk 10 minutes down the road to the relocated Barnes Foundation, allowed him to advance and deepen his conception of the “decorative.

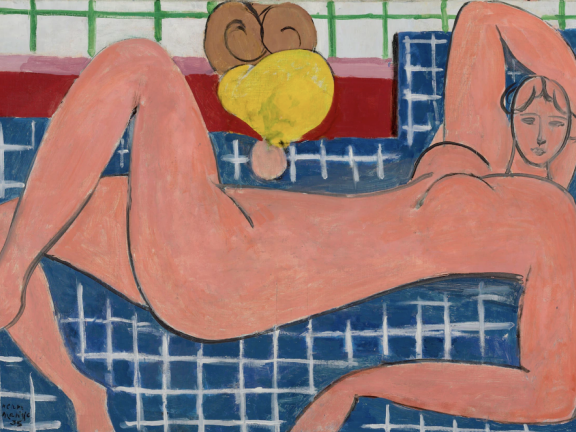

Matisse was focused on distillation in these years. He wanted to marry a sense of voluptuous sensuality with order and elegance — the Dionysian with the Apollonian. The first step was to flatten out the space in his pictures. Flattening the picture (as he had done in his pre-Nice paintings) implied giving negative and positive space equal weight. Negative space could now take on a more active role. More specifically, Matisse understood that if he wanted to combine a sense of living, breathing expansion with harmonious order, he would need to distort the contours and proportions of his figures until they were in just the right relationship with the space around them.

I have not mentioned color. But of course, it was all about color. One basic thing Matisse had realized was that color intensity was a function of size. A large area of blue was not just a larger area of blue, it was more intensely blue. That put it in a different relationship with the areas of color around it.

You can think of Matisse’s sophisticated, intuitive approach to color in terms of barometric pressure: He orchestrated areas of high pressure (smaller color areas, more visible brushstrokes and contour lines, more frequent alternations) with low pressure (larger, airier expanses of pure, unmodulated color) until he had balanced calm and turbulence, order and sensuality in just the right way.

The Philadelphia show kicks off with a prologue — a smattering of Nice period works, including the busily patterned “Odalisque With Grey Trousers” and the ravishing “Woman With a Veil.” Both accentuate background colors and shapes over the central subject, offering a preview of what was to come. The next section examines the Barnes mural and a commission to illustrate a book of Stéphane Mallarmé’s poems.

Subsequent galleries focus on Matisse’s easel paintings; his painted tapestry cartoons; pictures of his assistant and model, Lydia Delectorskaya; his collaboration with Léonide Massine and the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo; and the suites of drawings he made, in theme-and-variation mode, after an operation for abdominal cancer in January 1941.

The individual paintings, drawings and sculptures — it goes without saying — are insanely, almost unconscionably beautiful. But what makes the unfurling phenomenon of Matisse’s career so compelling is the struggle — or what the Greeks called “agon.”

In Greek theater, the “agon” describes the tension between the protagonist and the antagonist which, never reconciled, leads ineluctably to tragedy. (Ineluctable means “not to be escaped by struggling.”) You can find analogies for this “agon” in the tension in Matisse’s paintings between positive and negative space (with neither getting the upper hand) or, more broadly, in Matisse’s attempts to balance the Apollonian with the Dionysian.

But there was also — as there is today — a contest between Matisse’s harmonious, beautiful vision and the political sphere, with its ever-deepening rancor, ugliness and strife. The two things could not be reconciled. Nor could they be kept apart: Matisse’s beloved daughter, Marguerite, was tortured and interrogated by the Gestapo for her work with the French Resistance. She narrowly escaped death, unlike millions of others.

Matisse is profound. This show is sensationally beautiful. But just as Matisse worked hard to activate the negative space in his 1930s works, something about our present-day politics activates the historical background to this exhibition. I barely thought about it while I was in the exhibition, but in retrospect, there is something truly tragic about the apotheosis of so great an artist coinciding with baseness and barbarity on such a vast scale.

Matisse in the 1930s Through Jan. 29 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. philamuseum.org.